Today, Bank of England Governor, Mark Carney, announced that Alan Turing will appear on the new £50 polymer note. Making the announcement at the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester, the Governor also revealed the imagery depicting Alan Turing and his work that will be used for the reverse of the note. The new polymer £50 note is expected to enter circulation by the end of 2021.

Alan Turing was chosen following the Bank’s character selection process including advice from scientific experts. In 2018, the Banknote Character Advisory Committee chose to celebrate the field of science on the £50 note and this was followed by a six week public nomination period. The Bank received a total of 227,299 nominations, covering 989 eligible characters. The Committee considered all the nominations before deciding on a shortlist of 12 options, which were put to the Governor for him to make the final decision.

Alan Turing was the father of computer science and AI

Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, commented: “Alan Turing was an outstanding mathematician whose work has had an enormous impact on how we live today. As the father of computer science and artificial intelligence, as well as war hero, Alan Turing’s contributions were far ranging and path breaking. Turing is a giant on whose shoulders so many now stand.”

Alan Turing provided the theoretical underpinnings for the modern computer. While best known for his work devising code-breaking machines during WWII, Turing played a pivotal role in the development of early computers first at the National Physical Laboratory and later at the University of Manchester. He set the foundations for work on artificial intelligence by considering the question of whether machines could think. Turing was homosexual and was posthumously pardoned by the Queen having been convicted of gross indecency for his relationship with a man. His legacy continues to have an impact on both science and society today.

The shortlisted options demonstrate the breadth of scientific achievement in the UK, from astronomy to physics, chemistry to palaeontology and mathematics to biochemistry. The shortlisted characters, or pairs of characters, considered were Mary Anning, Paul Dirac, Rosalind Franklin, William Herschel and Caroline Herschel, Dorothy Hodgkin, Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage, Stephen Hawking, James Clerk Maxwell, Srinivasa Ramanujan, Ernest Rutherford, Frederick Sanger and Alan Turing.”

Sarah John, Chief Cashier, said: “The strength of the shortlist is testament to the UK’s incredible scientific contribution. The breadth of individuals and achievements reflects the huge range of nominations we received for this note and I would to thank the public for all their suggestions of scientists we could celebrate.”

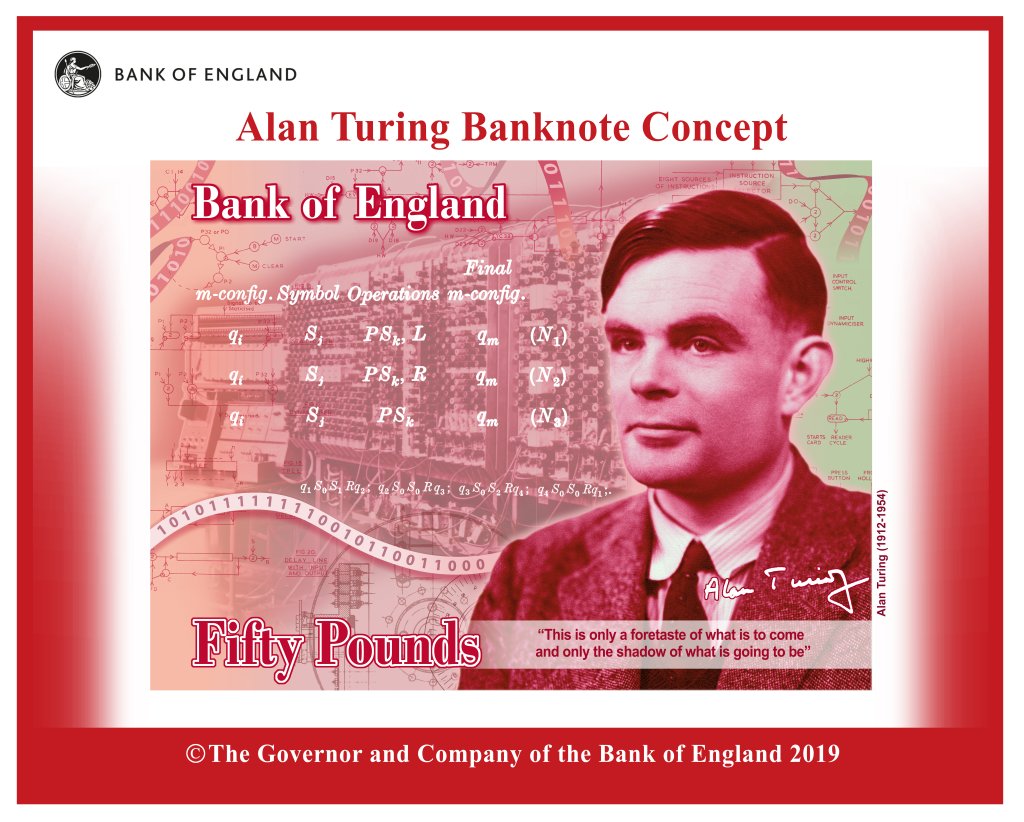

The new £50 note will celebrate Alan Turing and his pioneering work with computers. As shown in the concept image, the design on the reverse of the note will feature:

A photo of Turing taken in 1951 by Elliott & Fry which is part of the Photographs Collection at the National Portrait Gallery.

A table and mathematical formulae from Turing’s seminal 1936 paper “On Computable Numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem” Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society. This paper is widely recognised as being foundational for computer science. It sought to establish whether there could be a definitive method by which any theorem could be assessed as provable or not using a universal machine. It introduced the concept of a Turing machine as a thought experiment of how computers could operate.

The Automatic Computing Engine (ACE) Pilot Machine which was developed at the National Physical Laboratory as the trial model of Turing’s pioneering ACE design. The ACE was one of the first electronic stored-program digital computers.

Technical drawings for the British Bombe, the machine specified by Turing and one of the primary tools used to break Enigma-enciphered messages during WWII.

A quote from Alan Turing, given in an interview to The Times newspaper on 11 June 1949: “This is only a foretaste of what is to come, and only the shadow of what is going to be.”

Turing’s signature from the visitor’s book at Bletchley Park in 1947, where he worked during WWII.

Ticker tape depicting Alan Turing’s birth date (23 June 1912) in binary code. The concept of a machine fed by binary tape featured in the Turing’s 1936 paper.

Mark Carney was speaking at the £50 note character reveal press conference at the Science & Industry Museum in Manchester. He was joined in a panel discussion by Dr Demis Hassabis, Co-Founder & CEO of DeepMind and Sally MacDonald, Director of the Science and Industry Museum who unveiled an exhibition of the shortlisted nominees for the £50 bank note.

Alan Turing (1912-1954) – A brief background

Mathematician who is considered the father of computer science and artificial intelligence; he played

a pivotal role in the development of early computers and his code-breaking role within WWII was

instrumental in the Battle of the Atlantic and is widely believed to have shortened the war.

Alan Mathison Turing was born in West London on 23 June 1912. He gained a first class degree in

Mathematics from Cambridge University in 1934 before becoming a fellow of Kings College in 1935.

In 1936, aged 24, Turing produced a paper called “On Computable Numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem1

”Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society which included a description of a

computing device now referred to as a ‘Turing Machine’. This imaginary machine could read instructions stored in its memory to carry out any computable task. This paper is widely recognised as the theoretical basis of modern computers.

At the outbreak of WWII, Turing moved to the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park where he designed the British Bombe cryptographic machine. Turing’s team played a pivotal role in cracking the German Enigma code, previously seen as unbreakable. They decoded naval and U-boat messages, which revealed information about German positions and helped to shift advantage to the Allies during the battle for the Atlantic. Turing was awarded an OBE for his code breaking work.

After the war, Turing worked on designs for pioneering early computers including the Automatic Computing Engine (ACE), one of the first electronic stored-programme computers which was built in 1950 at the National Physical Laboratory in London. At Manchester University’s Computing Laboratory, he developed programming for the Ferranti Mark 1 computer, the world’s first commercially available electronic computer.

While at Manchester, he explored artificial intelligence proposing an experiment which became known as the ‘Turing Test’. A machine could be considered able to ‘think’ if a human interrogator was unable to distinguish a machine’s response from that of another human being. He also worked on morphogenetic theory, looking at the mysteries of patterns in nature for example trying to explain the existence of Fibonacci numbers in plant structures. His paper, ‘The chemical basis of morphogenesis’, has since been recognised as original and pioneering work.

In March 1952, Turing was convicted of Gross Indecency for his relationship with a man. To avoid a prison sentence, he accepted probation which was conditional on receiving oestrogen hormone, otherwise known as ‘chemical castration’. After his prosecution, he was no longer able to consult with GCHQ as homosexuals were ineligible for security clearance.

On 8 June 1954, aged 41, Turing was discovered dead by his housekeeper. His cause of death was

determined as cyanide poisoning and the inquest later ruled the cause of death as suicide.

In 2009, Gordon Brown made an official posthumous apology for Turing’s treatment and Turing received a royal pardon for the conviction in December 2013. In 2017, the ‘Alan Turing Law’, was passed that posthumously pardoned men cautioned or convicted under historical legislation that outlawed homosexual acts.

About The Science and Industry Museum

The Science and Industry Museum tells the story of where science met industry and the modern

world began. Manchester was one of the first global, industrial cities, and its epic rise, decline and

resurrection has been echoed in countless other cities around the world. From textiles to computers,

the objects and documents on display in the museum tell stories of everyday life over the last 200

years, from light bulbs to locomotives. The museum’s mission is to inspire all its visitors, including

future scientists and inventors, with the story of how ideas can change the world, from the industrial

revolution to today and beyond.

The Science and Industry Museum is part of the Science Museum Group, a family of museums

which also includes the Science Museum in London; the National Railway Museum in York and

Shildon; and the Science and Media Museum in Bradford. The Science Museum Group is devoted to

the history and contemporary practice of science, medicine, technology, industry and media. With

five million visitors each year and an unrivalled collection, it is the most significant group of museums

of science and innovation worldwide.