I owe a huge debt to my teachers, what they wished for me was often more than what I wished for myself. I arrived in England at a young age having been schooled ‘traditionally’ in Kenya – which meant not talking in class, speaking only when spoken to and learning times tables by rote. Failure on any count resulted in your knuckles or palm being thwacked with a thin cane. Naturally I became a quiet and studious girl. Shyness was also natural at that age as I came from a traditional Indian family, one with three girls and a boy. My brother was of course my parent’s favourite and the girls were brought up to be “girly” – demure, well-behaved, religious and homely – while my brother was the one allowed to be boisterous, rebellious and adventurous. The reality is that this type of traditional parenting imbues a lack of confidence, especially in girls. So imagine the shock when I arrived at a modern comprehensive secondary school in North London, UK, with over a 1000 girls! The school had just become a comprehensive having previously been a well-regarded grammar and I was fortunate that many of the former teachers remained the same.

I owe a huge debt to my teachers, what they wished for me was often more than what I wished for myself. I arrived in England at a young age having been schooled ‘traditionally’ in Kenya – which meant not talking in class, speaking only when spoken to and learning times tables by rote. Failure on any count resulted in your knuckles or palm being thwacked with a thin cane. Naturally I became a quiet and studious girl. Shyness was also natural at that age as I came from a traditional Indian family, one with three girls and a boy. My brother was of course my parent’s favourite and the girls were brought up to be “girly” – demure, well-behaved, religious and homely – while my brother was the one allowed to be boisterous, rebellious and adventurous. The reality is that this type of traditional parenting imbues a lack of confidence, especially in girls. So imagine the shock when I arrived at a modern comprehensive secondary school in North London, UK, with over a 1000 girls! The school had just become a comprehensive having previously been a well-regarded grammar and I was fortunate that many of the former teachers remained the same.

My attempts at higher maths were pathetic

Miss Samson was an Amazonian maths teacher who could have given Roald Dahl’s Miss Trunchbull a “run for her money”. Despite her stern appearance, thick ankles and penchant for tweed skirts she was actually a very kind person. I often saw her suppressing a guffaw at our pathetic attempts at learning higher mathematics and despite being only a B grade student at maths, Miss Samson got me through enough of the A/S curriculum to undertake science A Levels. As anyone trying to learn A level physics will tell you, without maths it can be pretty tough going.

We were like “lumps of lead”!

Miss Myers, a New Zealander who insisted we were like “lumps of lead” (solid and impenetrable, presumably) was another kindly teacher whom I remember. She was particularly supportive when I set fire to the front of my jumper and fringe with a bunsen burner – running out of the room screaming for Glyn Payne, one of the few male teaching assistants to come and give me first aid. I recall trying to assess whether I needed mouth to mouth resuscitation for singeing my fringe, but, decided that the subject was best avoided in case Miss Myers felt it was her due to perform that duty. I became a favourite of Miss Myers when she learnt who my elder sister was and given that my sibling studied chemistry at the University of Oxford…..well I certainly took advantage of that fame-by-association for a few years.

Do not sing “blow the wind southerly, southerly”!

I adored both my physics teachers: Miss Oakley who taught me the in the lower form years and Mrs Michaels who taught me at A level. Miss Oakley was a softly-spoken teacher with a particularly sharp intellect whose house I loved visiting as she had a piano on which she played classical music. My other physics teacher Mrs Michaels, who had the wild curly hair one imagines all physicists should have, loved old style songs like “blow the wind southerly, southerly”. I imagined this to be a glimpse of typical “Englishness”. When I had my own daughter, I decided to buy a piano and enrol her in classes from the age of five because of Miss Oakley’s influence. I love that my daughter can play and even though I excuse her from singing “blow the wind southerly, southerly”, just the sound of the piano is a joy! Mrs Michaels was also the mother of one of my friends so, of course, a cause of great curiosity. What were teachers like as parents?

Learning about loo brushes in biology

My memories of my biology teachers are bittersweet. They were the ones who first spotted that I was short-sighted, having to squint at the blackboard from the front row. A pair of standard issue blue NHS spectacles later did not endear them to me at all. I recall Mrs Blakeley, who also lived very near to us and had no problem in popping into my mother’s shop to break the news of my O level grade before I had been told about it. However, since it was good grade I forgave her enthusiasm, particularly after she had given us sex education classes and advised us not to consider the male penis like a loo brush. That vision and her beetroot red face from that lesson have stayed with me for years!

We often got personally involved with our teachers’ lives, not because of what they taught, but, because they lived near to us, bought from my parents shop, and we felt like we were part of their world. One year, Mrs Blakeley’s daughter caught meningitis and I recall looking up this disease and wondering about the depth of their fear and anxiety. Thankfully she recovered and life returned to normal even though worse was to come. During my A levels Mrs Bevan, a beautiful blonde-haired Biology teacher who played tennis at our local park, died of breast cancer. It was a case of being healthy before the school holidays and dying within a few short weeks after that. It was my first encounter of a death from cancer – a word that was barely spoken in our house except in a whisper.

East Riding of Yorkshire

I liked studying and remember telling all my teachers that I was going to study their subject at A Level. I told Miss Brooks, my geography teacher – who regaled us with stories about the beautiful East Riding of Yorkshire and gave us very serious meteorological projects like measuring rainwater and explaining cloud formations – that I was definitely going to study geography and visit South America. Some years later, when I actually visited East Riding of Yorkshire (never having made it to South America) and saw for myself the beauty of the hills and brooks, I had a pressing desire to write and let her know that it was exactly as she’d described it.

I remember Miss Vasey (although I don’t remember if that is the correct spelling of her name), a soft-spoken, blonde doe of a teacher who tried to teach us rebellious teens about English literature. I recall telling her that I would study English at A Levels after one particular class in which we had read far too much lasciviousness into a Ted Hughes poem. I could see her leaving puzzled, completely disagreeing with our interpretation of the poem, blissfully unaware that we were teenagers after all!

Miss Thomas, my RE teacher, was a sinusitis sufferer and I always assign that condition with piousness for that reason. Miss Thomas was not pious or particularly strict but the connection with nasal suffering and religious penance remains to this day. Perhaps it was her demeanour or long-sleeved ruffled blouses that made me associate her condition with the subject that she taught? Miss Walker, however, was a spectacularly good French teacher who was the quintessential Englishwoman so I learned that looks can be deceptive.

And then there was the glamorous Ms Fox whose aim was teach us history, but who actually taught us how to pick up great fashion items in the Blue Cross sale and how she always bought her coat at House of Fraser. I always envisioned that she would have made Henry VIII a most decorative wife!

Finding “my voice”!

From the outset, my teachers would not leave me to be the “lowest of the low” and the “quietest of the quiet” when this was all I wanted. My first instinct was always invisibility – I felt that if I said nothing, they would not remember I was there. This tactic failed spectacularly in the first week of senior school with Mrs Brown, the head of year who decided that the problem was obvious – I simply could not speak English! However, given that English was my first language this was irksome to an individual who was simply shy. I completed her task of writing a homework essay with a thoroughness and studiousness worthy of a pHD student and meekly handed it in. She thought I’d copied it from a book and promptly called me out of class to read a chapter from a novel chosen from her bookshelf. Mustering up what little courage I had, and cowering under the weight of my parents’ expectation of my speaking perfect English (my first language), I gave the first and only flawless performance of reading out loud. I am not sure who was more surprised. Mrs Brown for initially thinking I could not speak or read English or myself for having finally found “my voice”!

Teachers sometimes work under false assumptions

Life improved after that. I realised that although teachers sometimes worked under false assumptions, they were trying to help me improve, not become more invisible but less so. I gradually learnt to put my hand up in class even when I thought my answer was wrong; I learnt that occasionally there is no right answer, merely a perspective. My practical lessons taught me to organise, record and monitor methodically. My biology dissection lessons taught me to summon up courage and “get on with it”, they could be lessons in endless girly squeamishness or they could be a means to an end. Physics and Maths taught me to postulate ideas and work backwards to derive the necessary formulae to fit my hypothesis, usually incorrectly, but it was a valuable lesson in logic nonetheless.

History and RE taught me view the past with less myopia and more like a jigsaw puzzle with various events fitting neatly together to create an era. And Art was freedom. Freedom to visualize, conceptualize and be creative. While we were neatly screen-printing chintzy cushion covers, punk rock was redefining fashion, music and art in the wider world. Even though loving Art and being good at Art were two different things, the most valuable lesson I learnt was to look at objects in a different way; firstly, as they appear and then at them from different angles, with lenses and filters. To this day, my love of photography comes from a few lessons spent washing our own negatives and producing our own prints in a little darkroom at school.

Learning was a liberating experience

I don’t recall being competitive at school, although I do remember the opportunities it offered of glimpses into other realms. I once tried to convince my father to buy the entire Encyclopedia Brittanica, which cost a fortune at the time, because I thought it would be wonderful to have a library at home. I had seen the volumes in the school library and imagined that our social status would somehow magically change if we had a set at home. The free access to journals, books of all types, computers and recordings in the library was like a treasure trove – it was an escape from the conservative view that girls should be cleaning, cooking and tidying up which is what I would have to do if I wasn’t at the library. Unlike all other teenage girls “going to the library” didn’t mean smoking behind the cinema, meeting up with boys or drinking in the pub. For me “going to the library” actually meant going into a library and enjoying reading an uncensored book or looking at cartoons in a comic without the threat of parental disapproval. Learning was a liberating experience.

The Teachers’ Strike

And then there was the teachers’ strike. Lessons were cancelled and plans were laid to march onto the Houses of Parliament. Girls were told they could go home or accompany the teachers and so it was that I found myself walking around Parliament Square with a placard supporting a pay rise for my teachers. The protest march was large and loud and became my first brush with the media – a photographer from The Times snapped me and a few girls with the teachers and the placards and the “fall out” was felt at home for weeks. The image appeared in the paper and countless friends and relatives phoned my parents to tell them about it. My conservative parents were outraged that their daughter – whom they thought was in school learning important things – should instead be at a march protesting against the same British government that had given us citizenship and a home. For me, it was exciting and interesting. For them, it was a betrayal. A betrayal of trust, class and status – conservative, well brought up girls simply did not hold placards and attend protest marches. I wasn’t allowed to accompany my teachers anywhere without permission after that and had to return straight home after school for weeks.

My teachers continued to push and prod

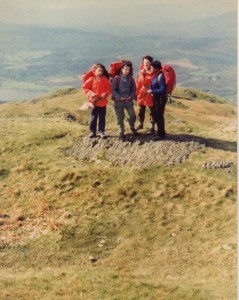

My teachers, however, continued to push and prod (I wish I could call it training) me into not confining myself docilely into a mould that my parents envisioned. They taught me to think freely; participate in lessons outside school; volunteer for new projects, undertake activities like the Duke of Edinburgh scheme and generally have a vista greater than that afforded by my family upbringing. Years later, when I think back I remember the names of my teachers and vividly recall all their ‘failures’ in teaching, which in themselves taught me a great deal, perhaps more than the curriculum itself. That is why I owe a huge debt to my teachers.

My teachers, however, continued to push and prod (I wish I could call it training) me into not confining myself docilely into a mould that my parents envisioned. They taught me to think freely; participate in lessons outside school; volunteer for new projects, undertake activities like the Duke of Edinburgh scheme and generally have a vista greater than that afforded by my family upbringing. Years later, when I think back I remember the names of my teachers and vividly recall all their ‘failures’ in teaching, which in themselves taught me a great deal, perhaps more than the curriculum itself. That is why I owe a huge debt to my teachers.